Call Center Cinderella Part I

Is Your “Biggest Branch” Your Best-Kept Secret?

By Edward G. Brown and Johanna Lubahn Cohen Brown Management Group, Inc.

For many industries, it comes as no surprise that call centers are powerful generators of revenue. But banking has a different history of lower expectations for call centers. A few banks are changing this, proving that clear, capable, and motivated agents can deliver differentiating service and highly profitable interactions.

In an impersonal, impatient world accustomed to emotionless interactions but craving the opposite, are you setting the standards high enough for your call center? Do your reps know how to find the right words, use the right tone, convey authentic emotion, and make sincere connections with your customers?

If not, this paper will show you why it is essential that you equip them to do so, and how some industry leaders are already doing so.

cover photo courtesy of Johannesburg News Agency www.joburg.org.za

A Secret Weapon

In today’s banking world, where CEOs are expected to deliver a differentiated customer experience AND a trimmer efficiency ratio AND organic revenue growth, they have a secret weapon. Sometimes so secret it travels beneath their own radar, its potential unexploited.

The secret weapon is the call center – the often lightly regarded, organizationally orphaned call center – where, it just so happens, most of the bank’s customers have their first interaction and where they often go when they are most at risk. Like Cinderella banished to the cinders instead of triumphing at the ball, call center potential is regularly underestimated.

In this paper, the authors – customer experience experts engaged with bank call centers around the world – pose a fresh set of questions for bank CEOs:

- Does it still make sense to think of your “biggest branch” as a cost center? To forego revenue because call centers “are only for service”? To tolerate an inconsistent customer experience between the branch and the call center?

- If not, what would it take to make the cultural change – not just to change the call center, but to change, well, to change you?

For many industries, it comes as no surprise that call centers are powerful generators of new revenue. According to McKinsey, in telecommunications, some companies generate as much as 60 percent of new revenues from the call center. For some credit card companies, the number is 25 percent.

That is not unheard of in banking, but it is rare. The call center director of one medium-sized bank set and regularly met a goal that would daunt most: keeping pace daily with the bank’s entire branching system. “We were 200 people in the call center, and there were 200 branches. We would make 50 percent of the sales every day – with one-tenth of the people and one-quarter of the cost.”

“We were 200 people in the call center, and there were 200 branches. We would make 50 percent of the sales every day –with one-tenth of the people and one-quarter of the cost.”

“In retail banking…we estimate that every five inbound service agents could generate as much new retail business as a mature branch.”

McKinsey again: “In retail banking…we estimate that every five inbound service agents could generate as much new retail business as a mature branch…. Efforts to cross-sell during inbound service calls could increase annual sales of new products by an amount equivalent to 10 percent of the retail sales generated by a bank’s entire branch network.”

Bank of New Zealand surpassed even that mark. The 2006 global silver winner for “Best Customer Service” in Contact Center World’s prestigious annual competition (topping all industries, not just banking), BNZ’s call center regularly delivers fully 35 percent of the bank’s retail revenue.

In today’s revenue-hungry environment, what are the options? Ramping up revenue via the new-branch route is a dicey proposition, more risky than improving call center returns. Thomas K. Brown, Chief Executive Officer of Second Curve Capital, calculates that of new branches opened at the beginning of the current branch boom in 2001, “The rule of thumb in the business is that a branch needs to have $25 million in deposits before it moves safely into the black…. By that standard, the numbers above are appalling. They imply that fully 70% of the bank branches opened five years ago are losing money.”

Contrast this to the call center where the cost of sales can be covered in the first hour of each day, and where employees are virtually never engaged in anything but talking to customers.

Another new revenue option – finding new customers – is not only difficult, sometimes it is not even an option. In the U.S. at least, many big banks are bumping up against the 10 percent maximum share of total U.S. deposits. By law, they are forced out of the attraction game and into the expansion game – into strengthening relationships with their current customers. Who other than tellers have more interactions with current customers – and thus more influence on the customer relationship – than the bank’s call center agents?

It is not just revenue potential that makes call centers loom larger today; there is the other half of the profit equation: expenses. As one financial executive lamented, “There is no end. No one has to ask me to cut my budget each year. We all just know that each year we will be expected to do more with less. If you are a revenue producer, you are expected to come up with more revenue every year, and if you are an expense saver, you are expected to come up with more savings every year. You never get a break from it.”

Typically, for the same number of sales, a bank call center takes one-tenth of the people and one-quarter of the cost of sales compared to the branch network. In the slim-margin business of banking, selling effectively through the call center should be an irresistible source of “free” profit margin.

There’s another compelling reason for maximizing the call center’s potential: the lost opportunity cost of the undervalued, under-trained, under-empowered employee. Large organizations like banks, which must find in their vast staffs the differentiation they can rarely sustain in their products, find that Peter Drucker’s warning has never resonated more strongly: “In the knowledge society, the most probable assumption for organizations…is that they need knowledge workers far more than knowledge workers need them.”

A recent Harvard Business Review article states, “Managers are fond of the maxim ‘Employees are our most important asset.’ Yet beneath the rhetoric, too many executives still regard – and manage – employees as costs. That’s dangerous because, for many companies, people are the only source of long-term competitive advantage. Companies that fail to invest in employees jeopardize their own success and even survival.”

Yet in more than a few banks, there has been a call center stigma. Managers cycling through the call center would make it a fast rotation, fearing a loss of personal visibility. It didn’t help that at many banks, call center revenues are often booked to the branches, leaving call centers holding only the expense bag. It didn’t help that call center managers, who often don’t see their profit and loss numbers, have trouble managing the center as a business or being compared fairly to their peers.

If the bank call center is viewed as a back-office cost center for keeping low-value transactions out of the high-cost branch flow, that perspective is probably reflected in many ways. Where – branch or call center – do you demand more talent and experience? Where do you pay more, promote more, train more? Where do you offer a better working environment and exercise more convincing employee retention methods? Where does the head of your branch system report? Where does your call center director report?

The reality is that no growth-minded bank can afford to squander a single resource, least of all the revenue potential of all those employees in its “biggest branch.”

Some Stubborn Myths

Yet despite evidence that call centers can significantly help close the revenue gap for banks, some stubborn myths persist at many banks that cause them to forego spectacular returns in revenue, customer loyalty, and employee satisfaction.

“In retail banking…we estimate that every five inbound service agents could generate as much new retail business as a mature branch.”

Selling IS service, if it means helping customers manage their financial health.

Myth #1: Call centers are for service, and selling undermines service.

Selling undermines service only if selling means canned pitches to disinterested or distressed customers, or product suggestions that reveal indifference to the customer’s financial situation, or taking advantage of a customer’s distress with one product to urge an upgrade to a more costly product.

But if selling means helping customers manage their financial health, then selling IS service. Patients don’t expect the doctor to stitch up a head wound but overlook the concussion, or to set a bone but ignore a weight gain. They are paying for medical care and expect the doctor, not the patient, to be the medical expert – articulate and generous with patient-specific insights and advice.

A few farsighted bank call centers are adopting this model and co-opting the myth. They are not only outperforming their branches on customer service, but also on leading indicators of sales success.

For Jane Nixon, beating the branches was first a benchmark for her agents to aspire to, and now it is a standing point of pride. Nixon is Outbound Manager for ASB, regularly ranked by the University of Auckland as the number one bank in New Zealand on customer service for both retail and business banking.

Nixon explains, “Our bank sample-surveys our customers, branch, and call center after the interaction. You can imagine our pride in the call center when, for two years now, while we were tripling the size of our call center, we not only exceeded our targets but also our branch network on two customer survey measures: our product knowledge and our ability to make the offer that suits their needs.”

“Make the offer that suits their needs.” That is selling. It is good medicine for a patient, and it is good service for a bank customer.

Myth #2: Customers don’t want to buy from call centers.

First, let’s never forget how the brokerage business used nothing but the telephone to steal away banking’s well-to-do, middle-aged customers just as they were building massive retirement accounts.

And recall that channel adoption curves tend to spike straight up after slow early stages. Research shows that already, at midsized banks, the combined volumes of online, voice-response, and call-center encounters are beginning to rival the number of teller transactions.

This myth did have roots in the traditional conflict between branch and call center that causes the branch system to try to retain “control” of customers. “Our products and services are too complex to be delivered via the call center. There’s too much turnover in the call center people. Our customers only want to do business face-to-face. Their service needs are just too important for the remoteness of the call center.”

But that conflict is dying a proper death in the face of the fact that customers are overwhelmingly under-served by any one bank. It is the rare bank that can boast a high proportion of heavily cross-sold customers; average cross-sell in banking is around two. That’s two products per customer in a business with scores of products and relationships going back years. Competition between channels squanders opportunities and frustrates the customers caught in the middle.

Customers want all channels. If that is an overstatement, it is still a good motto. It is abundantly clear that when banks treat their call center employees as professionally as they treat their branch employees, they record stellar performance: lower turnover, higher job satisfaction, higher service scores, and best of all higher sales to satisfied customers.

Bank of New Zealand, where the award-winning call center delivers 35 percent of the bank’s retail revenue, is a case in point. There the call center is actually a standalone business line called Direct Sales & Service, and its director Susan Basile is a General Manager who sits on the CEO’s Executive Committee. BNZ also has a true pay-for-performance model. But, cautions Basile, “Our remuneration system carefully balances sales and quality. It is unlimited on the sales potential side, but it is forfeited if quality falters, and individual quality standards are set very high.”

Myth #3: Call centers automatically track the right performance metrics.

Once again, call centers are captives of their history. Conceived to save costs – to get transactional calls out of the relationship-orientated branches – they in turn gave birth to productivity-laden measures and the systems to track them.

Walk into most sizable call centers today, and you will see something of a sports arena quality. Scoreboards posted high, flashing the latest productivity statistics – all where managers and agents can keep an eye on them and pace themselves accordingly. Average answer time, agent availability, average handling time, average talk time, average calls per hour, abandonment rate, longest wait time, shortest wait time, agent-answered volume, IVR-answered volume, and so on. Two minutes per call is a common call center limit. (What is the standard time limit for branch personnel? How often do they wrap up a service interaction in two minutes?)

Let’s never forget how the brokerage business used nothing but the telephone to steal away banking’s well-to-do, middle-aged customers just as they were building massive retirement accounts.

“We don’t want to waste customers’ time, but if we were to ask them what they most wanted from our call center, they might well say quick answers, but we’d be wrong to conclude they want fast talkers or hurried conversations.”

If you can only manage what you measure, and all your measures are about speed and call volume, then the only levers you can pull are those for faster calls or fewer calls. But if your job is to manage sales, referrals, and customer satisfaction, what metrics do you need? That is where many call centers find themselves struggling to capture the most basic data: how many sales, referrals, escalations, and callbacks. Few call center agents have the systems to support these basic data-capture needs. We often find agents tracking them with check marks on paper. Or flipping through several screens to find the answer. Or taking seven keystrokes to answer a call. If metrics matter, capturing them needs to be part of the process, not a sideline.

What does it tell your agents if you preach customer experience but measure length of call? BNZ’s Basile rejects the whole contradiction. “What do fast calls have to do with great conversations? We don’t want to waste customers’ time, but if we were to ask them what they most wanted from our call center, they might well say quick answers, but we’d be wrong to conclude they want fast talkers or hurried conversations. Our agents don’t even see their speed and volume stats.”

Basile sees those stats all the time, however, and she uses them to improve service. “If we see an agent’s calls are going longer than normal, it’s our job to see if there is a pattern, if the agent needs more coaching on identifying the problem faster or navigating to the right solution faster. Or maybe it’s a new campaign or a business line conflict that creates complexity. But ‘hurry up’ doesn’t improve the customer experience, and it certainly doesn’t promote sales.”

Myth #4: Call centers are call centers.

Call centers are call centers the way Starbucks is a coffee shop.

Well managed call centers are vibrant customer contact points, rich with potential, where customers go when they need acute care. Even with skyrocketing use of online banking and the spread of branches, when customers have a problem, they look for a phone number, and when they call it, they look for a live person.

Fielding hundreds of interactions a minute, often at critical junctures in the relationship, call centers are contained, disciplined, high-tech environments where new tactics can be deployed rapidly in measurable ways, trends tracked, employee competence assessed, and customer reactions measured. They are theatre – highly charged, lively concentrations of trained performers, focused on achieving positive outcomes. Rare is the branch, with its multiplicity of duties, that can match that contagious energy.

But how many call centers look that way? We visit call centers for a living and can usually tell on arriving what kind of experiences customers are getting. Many are found in dreary

locations – housed with the bank’s data and operations center, or in the local warehouse district. Little or no signage usually, and hardly ever does it say “(Proud) Bank Call Center.”

Let’s put a finer point on it. Call centers are customer-employee contact points. Half the equation is the employee who is expected to deliver an informed, polite, thorough, pleasing, differentiating customer experience. Yet how many banks concentrate on the call center employee experience?

Most have given up the old hot-desk environment, giving employees their own workspace, but few have invested in creating the kind of environment that attracts talented people. If your attrition is running high, compare the surroundings of your branch sales people to those of your best call center people. Have your call center employees overheard this: “They don’t get any walk-in customers, why would we invest in the appearance of the place?”

Call center employees are often shorted in more stunting ways. They are shorted on the skills that can help them deliver a good customer experience. The training they do receive often reveals a paradox. Sales training that equips them with little but stock phrases. Product training that equips them with little but jargon. Scripting that equips them with accurate but ineffective spiels. Perfunctory coaching that may or may not address their needs or the bank’s desired outcomes.

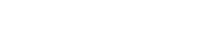

Our own mystery shops of bank call centers reveal that paradox: high marks on a few measures, but stunning drop-offs on basic sales steps.

% Of Call Center Employees Exhibiting Desired Behaviors

Fully 89% introduced themselves by name and 79% warmly greeted the customer. But only 31% asked for the customer’s name, 22% consultatively handled the immediate request, 20% presented solutions and benefits, and 16% attempted to gain the business. A dismal 6% obtained contact information for follow-up, and only 5% asked needs-identifying questions.

Call centers are customer-employee contact points. Half the equation is the employee who is expected to deliver an informed, polite, thorough, pleasing, differentiating customer experience.

“You must take your employees on every step of the journey with you. Dissatisfied employees will not have great conversations with customers.”

If you truly believed that every five of your call center agents could and should deliver sales results equal to those of a mature branch, you would make sure they were crystal clear on their goals. You would make sure they were fully capable of accomplishing them. And you would make sure they were fully motivated to do so. Clear, capable, and motivated: That is the success triangle that allows ordinary call center employees to achieve extraordinary results.

If call centers are customer-employee contact centers, they need to be treated that way. As online banking grows, the stakes are only increasing for how banks handle customers in remote situations. Online banking’s success will depend on employees who not only have product knowledge, but are also skilled in sales, customer engagement, writing, and typing. Maximizing the potential of call center employees is a good place for striving to prove that highly skilled employees can remotely deliver a consistent customer experience.

Five Traits of High-Performing Call Centers

Is your call center positioned for superior performance? In our experience, high-performing call centers typically evince five traits.

1- High-performing call centers have a vision.

They have a vision and talk that way. They have a broad view of the excellent call center as a business of the bank in which people, process, and technology are fully aligned. They don’t talk about IVR technology one day, then bring up employee hiring practices that afternoon, and take up sales training the next.They help their teams stay the course regardless what distractions arise. They know how their vision carries out the broader corporate strategy. They know how it carries out the customer strategy. They are continually assessing the center’s strengths and weaknesses and making necessary adjustments. They don’t make changes for the sake of change, but only when it supports the vision.

2- High-performers focus on employee satisfaction.

Top performers live and breathe employee satisfaction. If every customer touch improves a customer relationship or diminishes it, employees need to feel the same level of satisfaction in their jobs that they wish to impart to customers. BNZ’s Basile says, “You must take your employees on every step of the journey with you. Dissatisfied employees will not have great conversations with customers.” That is the people part of alignment with the strategy. At high-performing centers, agents know the value of every conversation and how to differentiate themselves on every call.

3- High-performers don’t just train, they embed skills.

Top performing call centers don’t hold agents accountable for demonstrating their skills while giving their leaders a pass, as though skills matter less on the way up. Good leaders want to continually refine their skills, and reinforce them. Not just once – not a perfunctory, “There, I’ve been trained; that’s over.” And not just, “They’ve been trained; surely they get it.” Top performers at every level in call centers recognize the virtue and value of continuous learning. They know it is a never-ending process. They overcome the time challenges by going beyond training and putting in place strong reinforcement processes.

4- High-performers focus on customer satisfaction, retention, and loyalty.

Top performers measure performance by desired results, not by effort expended. Client satisfaction is a significant measure, so are retention and loyalty. Top performers track these measures. You hear it in their ordinary conversations, not just in their weekly meetings.

When they encounter significant trends in either direction, they dig deeper to understand why, and they build processes around them – to replicate the positive trends and to stem the negative. They make customer satisfaction the primary topic of team conversations – not just one agenda item on the checklist. They try to take the view of the customer and challenge the way things are being done: “If we were the customer, what would we want done?

5- High-performers value technology as a resource, not the answer.

Top performers make technology their friend, but always subservient to the vision. They regularly assess how the technology is working for them: Does the IVR have too many options? Are they logically sequenced? With a new campaign, could the customer get trapped in an IVR menu?

Top performers know that voice technology can be a marvelous tool for customers who want to solve a problem quickly, or it can leave them shouting insanely, impotently at a recording. They consider, test, and deploy with caution and get regular customer feedback. The test: Does this suit our vision, and does it improve things for the customer?

Summary

It took the perseverance of a smitten prince and his whole retinue for Cinderella to live up to her potential. You don’t have to believe in fairy tales to believe a bank’s call center has enormous potential – that it can and should take its rightful place in your sales growth plan. It can go from being a “call center” to a revenue-generating customer experience center.

You just have to believe in the power of clear, capable, motivated employees – a belief made easier by the proven results at several successful banks. Their experience provides guidance for others who wish to lead a similar change.

Top-performing call centers make customer satisfaction the primary topic of team conversations – not just one agenda item on the checklist.

Edward G. Brown is President, Co-Chairman, and co-founder of Cohen Brown Management Group, the leading sales and service culture change specialist for the financial services industry. The company’s clients, many of the largest financial institutions on six continents, regularly report breakthrough results in revenue, cross-sales, customer service, and employee satisfaction. He created the company’s call center solution – a rich integration of classroom instruction, video, and real-world online experience for superior performance in all aspects of call center agent-customer interaction. He is the author of two books on management. Before founding Cohen Brown, he was a management consultant to Fortune 500 and other companies. He is currently focused on Breakthrough Behavioral Embedding, a new suite of solutions for ensuring superior performance.

Edward G. Brown is President, Co-Chairman, and co-founder of Cohen Brown Management Group, the leading sales and service culture change specialist for the financial services industry. The company’s clients, many of the largest financial institutions on six continents, regularly report breakthrough results in revenue, cross-sales, customer service, and employee satisfaction. He created the company’s call center solution – a rich integration of classroom instruction, video, and real-world online experience for superior performance in all aspects of call center agent-customer interaction. He is the author of two books on management. Before founding Cohen Brown, he was a management consultant to Fortune 500 and other companies. He is currently focused on Breakthrough Behavioral Embedding, a new suite of solutions for ensuring superior performance.

Ed_Brown@cbmg.com, (310) 966-1001.

Johanna Lubahn is neither a bean counter nor a bean harvester, but a contact center sales and service expert and Cohen Brown’s Managing Director for Contact Center Services, working with banks and bank contact centers around the world. Her clients are pleased to learn how they can remove the obstacles that would otherwise make their contact center representatives rushed, routine, and robotic.

Johanna Lubahn is neither a bean counter nor a bean harvester, but a contact center sales and service expert and Cohen Brown’s Managing Director for Contact Center Services, working with banks and bank contact centers around the world. Her clients are pleased to learn how they can remove the obstacles that would otherwise make their contact center representatives rushed, routine, and robotic.

Johanna_Lubahn@cbmg.com, (310) 966-1001.